Is Streets of Rage 3’s Music Bad or Different?

Welcome to Game Music Jobs! I am Munchman, a Game Music Jobs contributor.

This article is part one of a two-part investigation about the obscure origins of Streets of Rage 3’s music.

We all know the sound, as our heads bob to the slick chip beats that are nostalgic for some and a contemporary delight to others. Yes, I am talking about the music from the Streets of Rage game series.

I know what you are thinking. Who is this philistine to criticize the genius of pioneering composers Koshiro and Kawashima?

I am wounded; the very idea of Munchman insulting two of his favorite composers is about as plausible as your surviving nightly street fights and finding health-restoring therapeutic roast chickens under random garbage cans.

I will be doing some detective work to figure out what changed the musical style of Streets of Rage 3 (SOR3). Just call me Detective Munchman!

Put your torches down and hear me out. I am not casting aspersions on the music of Streets of Rage 3, but there are noticeable differences between the musical style of the first two games and the style of the third. I want to explore the differences, OK?

I am your gumshoe. Let the investigation begin!

First, we will explore a brief history of the first three games, and after that, the backgrounds of the composers.

It was 1991; Tom Kalinske had just replaced Michael Katz as CEO of Sega of America, and Sega’s Genesis was outselling Nintendo’s SNES by two to one. In line with Sega’s in-your-face risqué marketing campaign that appealed to older gaming demographics, a game was released in 1991 that was the exact personification of their cheeky marketing aspirations: Streets of Rage (SOR).

The first Streets of Rage game was developed and published solely by Sega; this beat-‘em-up game was ahead of its time in its graphics and soundtrack and enjoyed a unique relevance because of the politics of American inner cities around this time. The game’s subdued and muted colors and shadowy nooks of danger bridged the evening news narrative of increasing crime and insecurity and gave those in more mundane circumstances a vicarious thrill of perilous non-peril.

The game was a huge success, leading to the development of its second installment, Streets of Rage 2 (SOR2). There were multiple development companies involved in this project, such as Sega, Shout! Designworks; M.N.M. Software; H.I.C.; and, most notably, Ancient. Ancient was founded by Yuzo Koshiro; his mother, Tomo Koshiro; and his sister, Ayano Koshiro. This arrangement gave Koshiro more creative input and made a lasting impact on the musical direction of SOR 2 and the game audio industry. SOR 2 added two additional characters, and Ayano Kashiro and her husband, who were the character and graphic designers, led the visual development for the game and made the characters’ sprites larger and added more detail to the environments. The second game also hosted a second composer, Motohiro Kawashima, who, like Koshiro, was a young Japanese composer cutting his teeth on the game audio biz.

Streets of Rage 3 was released in 1994 and featured enhanced thematic scenarios, rapid gameplay, and a more complex storyline. It received relatively good reviews and was the only successor for more than twenty-five years. The only two developers on the project were Sega and Ancient.

THE COMPOSERS

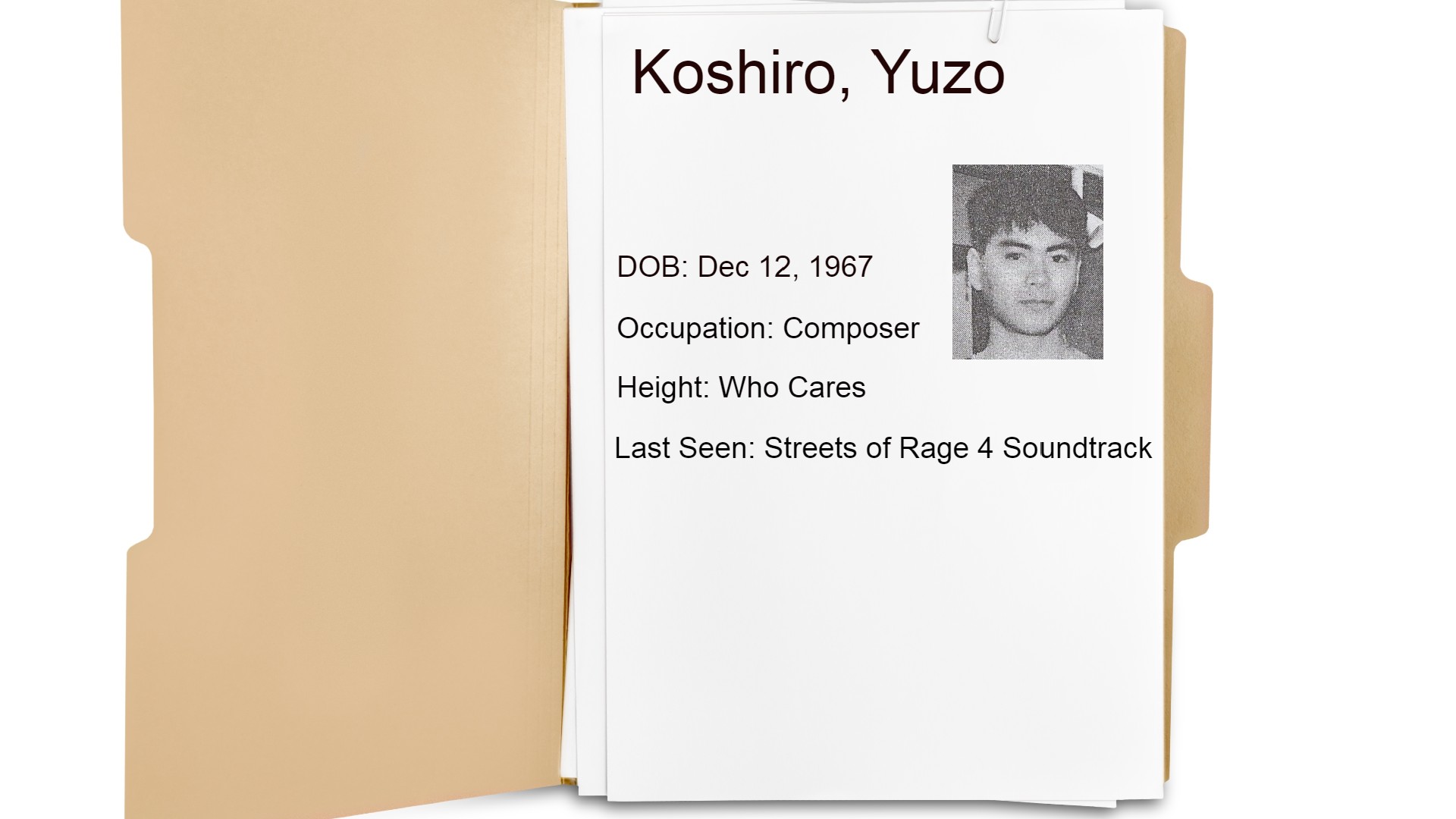

Yuzo Koshiro was born in Tokyo on December 12, 1967. He received piano lessons from his mother at the early age of three and later between the ages of eight and nine years old began to take music lessons from the young composer Joe Hisaishi who taught him for three years. Although Koshiro had some formal instruction in his early years, he is primarily a self-taught musician.

From a young age Koshiro broadened his musical scope. For example, he had an affinity for the classical music he grew up listening to and playing, but when his father played contemporary music, he did not like it much, though he grew to appreciate it. This attitude of expanding musical appreciation would become instrumental in the composition of some of his most exceptional work.

As a self-taught musician, he fine-tuned his composition skills by transposing jingles from his local arcade on a NEC PC-8801 computer a friend of his owned. As with most autodidacts, his advancement was not measured by the completion of semesters but by self-discipline; self-discovery; and honest, constructive criticism.

Koshiro got his start in game audio at eighteen years old in the summer of 1986, when he wrote a large stock of songs, and upon noticing a job ad for Nihon Falcom in a game magazine, he applied and was surprised he got the job. He worked for Nihon Falcom for two years before leaving to become a freelance composer. In 1988, Koshiro went to Los Angeles and gained increased exposure to the cultural origins of American music. As a freelancer he worked for Sega, for the Shinobi series, and the first SOR.

Koshiro is a natural composer who is able to absorb more than just the practical structure of chords and rhythm; he also seems to understand the feeling and spirit of a genre—and this is an ability that cannot be taught. It is this ability that allowed him to go from being completely unfamiliar with house music to becoming one of its progenitors in the video game genre.

Next, we will present a Techno addict named Motohiro Kawashima. He was born in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture, Japan, the son of a composer and conductor, and is a graduate of the Kunitachi College of Music, which is also the alma mater of Joe Hisaishi. Kawashima grew up in a music-loving family—his father introduced him to classical artists and popular ones too, such as Isao Tomita and Wendy Carlos.

As a child, Kawashima was mesmerized by the music of George Gershwin, particularly Rhapsody in Blue’s album cover, which formed a permanent link in his mind between music and city life. This link fueled his love of “Black” or “Urban” music.

He moved to Tokyo at the age of twenty-two and became enthralled by the sounds of techno at the age of twenty-three after hearing it in a CD-rental shop in Kichijoji called “33.”

Kawashima attended Kunitachi College of Music’s theory department, which offered training for musicologists, at the behest of his father, who warned him of the difficulties of making a living as a composer and suggested he receive an education with more job security.

In his fourth year at the Kunitachi College of Music, Kawashima-san started composing music for Ancient after an introduction through Yuzo Koshiro’s mother, who had an affiliation with the college. He and Koshiro became fast friends through their mutual love of bass-heavy music and went on nightly outings after their weekly meetings. They were mildly competitive with each other and tried to outdo each other’s compositions—as in a sibling rivalry.

The first games he worked on for Ancient were Gamegear’s Shinobi II and Batman Returns. To his surprise, Yuzo-san requested his help writing the music for Bare Knuckle 2 (Streets of Rage 2). This shows how much trust and confidence Yuzo had in Kawashima’s compositional skills.

That concludes part one of our two-part article. We will complete our investigation next week.

Do you make music similar to Streets of Rage 1 and 2? If so, share a link in the comment section.

Read Part 2 Here: PART 2